Working with licenses

0ne of the remarkable things about the launch of Everyday Heroes were the eight Cinematic Adventures offerned in the initial Kickstarter. When Dave first approached me about creating the game, he told me he intended to have a bunch of movie licences. I was surprised and unsure what to think about that. There are plenty of licensed games, but for one game to have eight movie licences for its launch was something I’d never seen. At that time, the slate of films wasn’t yet certain, I only knew I had to make a game that would follow in the footsteps of d20 modern, use the 5e rules, and be able to easily work for a whole host of unknown modern action film worlds.

When the Kicstarter was announced, many who saw it questioned if it was real. Since I was on the inside, I knew it was a very real deal as by then, the contracts were all in place. It definitely made the launch of Everyday Heroes something special and generated a lot of initial interest. To this day, fans love to speculate about future licenses and have asked a range of questions about licensing for games. I wanted to take some time to write about my experience working with these licenses and answer some common questions I see from reviewers and fans about them.

How licenses work

Every license contract is different, and I can’t disclose any actual terms from licences used at Evil Genius Games, but I can discuss some of the types of terms such agreements typically include.

Licenses are generally limited

Most licensing agreements have a limited duration. The licensor grants the licensee the right to use the intellectual property for a given period of time and for a given scope of use. For a game, this typically means the rights to make and sell a game for a fixed period of time. An unfortunate consequence of this is that it may be difficult to purchase a game once the licence expires since the company is no longer allowed to sell it. You must either find a retail outlet that has them in stock, or find one on the second hand market. For digital products this can be especially difficult, as they aren’t generally re-sold or held in stock by sellers as storefronts are essentially consignment based. Generally, this works out fairly well for the licensee as most games do the bulk of their sales close to their launch and from there, sales gradually drop off.

Licenses cost money

It almost goes without saying, but the licensee almost always pays the licensor to use the license. The cost of a licence is negotiated individually rather than having a set cost. Typically Licensors want to be paid a mix of an up front guarantee and a cut of the overall sales, often with the upfront being an advance on the sales commissions. This upfront cost means that a license can be a risky proposition. Low sales can mean it is impossible to recoup the guaranteed cost of the license. It also means that past a certain point, the licensing cost is a predictable percentage of the expected full sales price for the product. This can have a side effect of making it difficult to effectively discount a licensed product since the expected licensor fee is based on the full retail price. This kind of term is necessary to try and avoid a licensee circumventing full payment by giving away the licensed product for free or as a cheap promotion.

The limited time frame is typically there to preserve the value of the licence for future use. If you licence 20 different RPG makers, then the competition between them makes the licence less valuable to each of them. By limiting the time frame the license can be used, it ensures that those interested in it will pay well for it as they get exclusive access to it in their market. Licenses can be extended, but unless the licensee has a continuous supply of new products, the upfront costs to renew are often too high to justify the level of future expected sales.

The obvious benefit of licenses is that the licence will bring in more customers than a similar product that doesn’t have that licence. That increase in volume needs to be large enough to offset the increased cost per unit. There are also secondary effects that can raise the publisher’s overall profile, which can lead to increased sales of not only the licensed product, but also for other products the publisher sells. Deciding the ultimate value of a licence can be quite difficult.

Licenses are not pure profit for the licensor, they usually have to invest money into paying legal costs to have contracts created, to negotiate with licensees, and to carry out their responsibilities in the contract. They also face risks of non-payment, lawsuits, and other possible complications.

Licenses come with oversight

Every licence usually comes with some kind of approval process where the licensor must approve the use of the license by the licensee before the public sees it. License holders have a strong incentive to protect the value of the license by making sure it is represented well by the product. By default, licensors want the licence to be presented well, such that it enhances the value of the license, or at a minimum preserves it. Because approval is a common challenge with licenses, license agreements usually specify details about how the approval process should work and what the responsibilities of each party are in that process. Exactly how involved the licensor get’s is generally up to them. Some will be very exacting and hands on, ensuring every detail is just so, while others will only want to make sure there is nothing inappropriate in the product and that it presents the licence in a good light.

This oversight process is a cost of licensing for both the licensor and licensee. It takes additional design time for the licensor, and usually means a product will take longer to reach the market. The licensor must pay someone to review and approve materials. This is one reason licenses are almost never free or given without an upfront guaranteed payment.

How DO you get licenses?

The process of acquiring a license can be pretty easy or excruciatingly difficult. Most people assume that a licensor goes out looking for a specific license, but its also the case that a licensor may ask a license holding company what licenses they have on offer. The advantage of the second strategy is you know that these are properties someone is actively interested in licensing and holds clear rights to. When you have a specific licence in mind, there may be a number of barriers you have to overcome. First you have to find out who owns the license, which can be challenging. Next you need to make contact with the licence owner, which can also be challenging. Finally you need to persuade them to offer you the license, which can vary from easy to impossible.

Generally speaking, the larger the organization that holds a license, and the more valuable that license is, the harder it is to reach an equitable deal. Game companies typically don’t do the kinds of sales that a major licensor like Disney or Sony would be interested in. The costs in time and attention would be far greater than the licensor could ever afford to offer them. The exception to this is when the licensee is actively looking to promote the license.

There are companies and agencies that specialize in handling licensing deals. Some of them are companies specifically designed to acquire and license intellectual property, while others are established IP producers that want to either keep their IP in the public eye, or wish to make additional income from those IPs in media they don’t specialize in. Licenses managed by these kinds of companies are often easier to get since the license holder already has a contract ready and staff dedicated to managing them. That said, they may be priced to include the cost of that specialized overhead. There are also third party agencies who specialize in finding and making licensing deals, but like any professional their services will add to the cost of the licensing.

My Experiences

My personal experiences working on licensed properties is almost entirely positive. I felt very honored as a writer and game designer to be trusted with these licenses, and I took it as a personal mission to do them justice and leave the license better than I found it. For each of the licenses I tried to make sure I understood the limits of the license agreement and to do extensive research on the IP. I never relied on my memory and started each project by watching the films involved, reading the comics, and pouring over fan WIKIs. I didn’t just want to rely on what I love about the setting, but to dive into what other fans love about it. I wanted each product to feel like a love letter to the IP and a fun game to play.

I only rarely interacted directly with the licensees. Typically, I would do my work, then send my manuscript to the producer or the owner who would pass it to the licensee. They like to have a single point of contact so that the contract terms are followed, and communications are kept as simple as possible. From there, I would get back a set of notes with changes or concerns. Typically, I would simply make any and all changes requested, and these were typically very reasonable. Highlander was the only project where I decided I needed to push back on a request. I’d written the rules to say that an Immortal can sense when they are on holy ground, something not seen in the film. Naturally the licensee pushed back on this since it was a new element to the world unsupported by existing cannon. I wrote a lengthy response explaining that for players in an RPG to respect the rule about holy ground, they needed some way to know what was or was not holy ground and some serious consequences for fighting there. Otherwise, that aspect of The Game just wouldn’t come through in play and it would feel less like Highlander. I was happy that they well understood the argument and agreed, provided that I explain that this element of the game rules were not considered cannon for the world of the film, something I’d suggested in my initial response. Far from being a problem, this felt like a great collaboration between myself and the license holders to benefit us both and protect the world of Highlander.

My favorite license to work on was Escape From New York, largely because it is much less well defined as a world than the other films I worked with. There were a lot of world details needed for the game that are entirely absent from the films, comics, and novelization. I was very fortunate that the license holders were very happy with everything I’d invented to flesh out the world, its history, and the many other details I included in the book. While most of the licenses involved me detailing rules for what already exists in the lore, the vast majority of what is in Escape From New York was my own invention, inspired by the contents of the film and the zeitgeist the film was based on.

Beyond the licences we published games for, I had a lot of fun writing pitches for licenses we didn’t end up getting or following through with. For every license we did do, there were quite a few more we didn’t do. Sometimes it was because the terms of the deal just couldn’t work, and other times we just decided that the value of the license wasn’t worth the cost. Of course, if you have followed Evil Genius Games, you may know about the Rebel Moon license. If you haven’t kept up, the licence ended in a lawsuit between Evil Genius Games and Netflix that was eventually settled out of court. I can’t really speak to it in great detail because it’s not my story to tell and I agreed to keep sensitive matters confidential. Suffice to say, it ended in disappointment all around. That said, it was a lot of fun to work on as a writer and designer. We had the unique opportunity of working directly with Zack Snyder. That’s a rare treat in the world of RPG licensing, and he was truly fun to collaborate with.

Ultimately, I’m very proud and honored to have had the chance to work on these properties and I have been delighted by feedback from fans who really enjoyed the books. Often, the bigger a fan they are, the more they seem to appreciate my work. That makes me very happy.

Would I Do it Again?

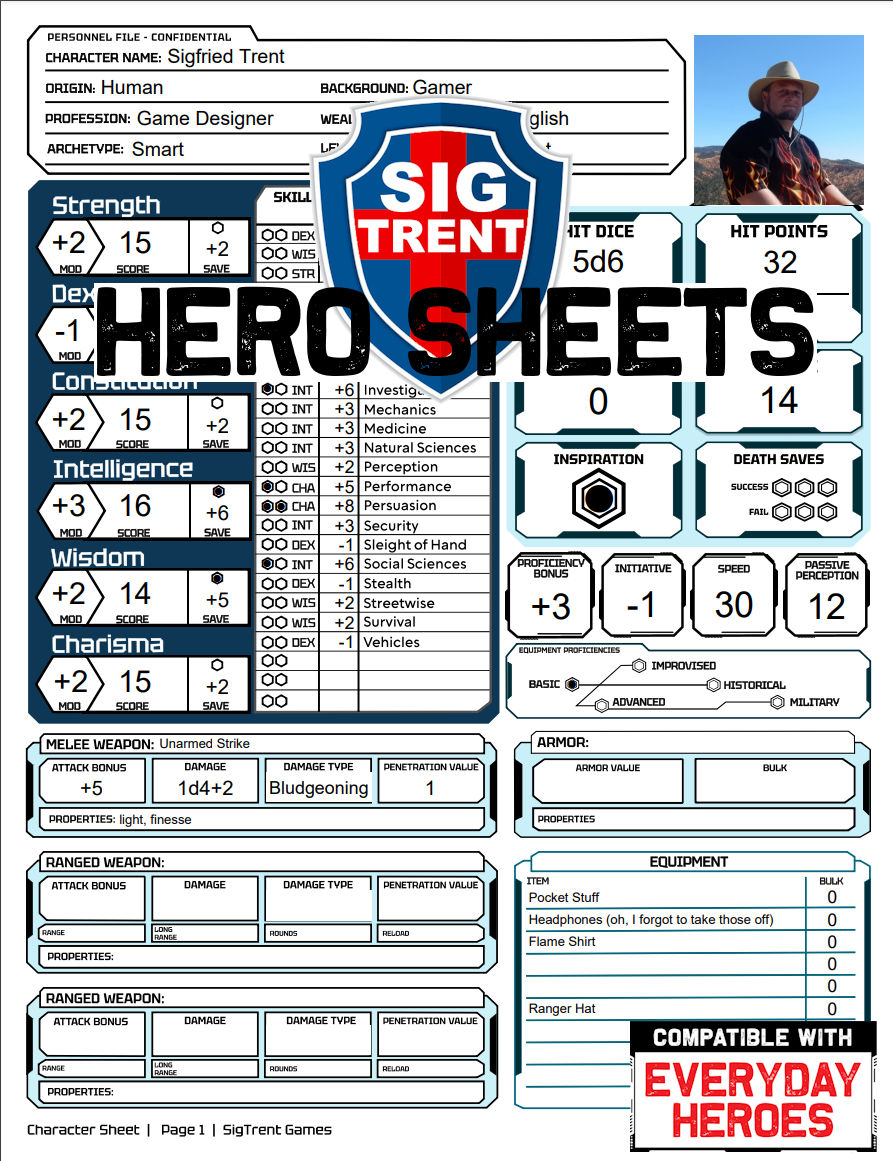

Absolutely! It’s unlikely SigTrent Games is going to be doing any licensed products,other than our Everyday Heroes License any time soon. The costs, risk, and logistical needs of doing a licensed game are simply beyond what I can manage alone. That said, as the company grows, and if we find good success, I would definitely like to leverage what I’ve learned to create some cool licensed games. Furthermore, if I get a freelance offer to work on a licensed property, I’m very likely to take it on given how much fun I’ve had with them in the past.